You’re Not Broken (but the system is): Sacred Activism as a response to Cultural Trauma

While much of the nation watched football and ate green bean casserole, we are gathered on the beach under a crisp clear blue sky to the sound of drums and the tide lapping the shore. I am here with fifty or so others on Thanksgiving Day by invitation of the Protectors of the Salish Sea (POSS), an indigenous-led coalition seeking policy and cultural changes to address the ecological crisis and preserve native cultures in the Pacific Northwest and beyond. POSS initiated a series of direct actions at the state capital last fall, calling on Governor Jay Inslee to declare a Climate Emergency and follow through on campaign promises in collaboration with Indigenous leadership in response to the ecological crisis. Today, reclaimed by east-coast native activists as a National Day of Mourning, is the latest of these actions. It is a fluid day of prayer, ritual, conversation, story-telling, connection, natural beauty, ancestral acknowledgement, peaceful demonstration, and finally, feast—potlatch.

These spacious attributes weave together to embody in a day what Chicana feminist theologian Gloria Anzaldúa might have described as Spiritual Activism: that is, “spirituality for social change, spirituality that recognizes the many differences among us yet insists on our commonalities and uses these commonalities as catalysts for transformation.” Spiritual Activism is a “path of two-way movement—a going deep into the self and an expanding out into the world, a simultaneous recreation of the self and a reconstruction of society.” It is “a spiritual practice…of always being attuned to one’s own self and other relationships—both human and non-human.”

In my experience, this is powerfully exemplified in the activism of POSS. After a period of congenial mingling, we gather in a large circle for opening prayer. One elder walks the perimeter of the circle, smudging each of us with sage; another elder and founder of POSS, Paul Wagner, stands in the center of the circle, greets us and prays for us in his native tongue. I quote him at length here (with permission), because words matter and the words of indigenous elders all the more so. There is already a different tone to this gathering than the average protest or direct action. Paul’s posture is one of a gentle quiet strength, his expression gracious, humble, and good-humored. He has a story-teller’s poetic inflection as he thanks everyone who has assembled:

I haven’t seen anything good become of this day until today, and that feels really, really, really, really good, I have to tell you. Today is a super beautiful day! To see your faces, to see you care, to know that you care, that you stand for the things that we stand for and that you’re willing to stand beside us and fight for prayer, come together with a prayer and bring a wellness to our children’s future, bring a wellness to our salmon’s future and our culture’s future. And so. I’m thanking each and everyone of you…

Paul tells some of his own personal and cultural history, and speaks to why we have gathered to be here. What seems central to the kind of story-telling that happens in Spiritual Activism is that it makes visible the hidden or ugly truths, and speaks the unspeakable—re-membering (that is, putting back together) the pieces of history that have so frequently lain obscured by white-washed versions. Paul shares:

We have one house here, Mother Earth. In those days we were one house inside of a long house, now we are in one house in Mother Earth…we gotta keep this house in good shape…And those schools, colonial schools I went to in Redmond WA, probably the best funded places in all America. They never taught any of these things to me. They only tell you to be a better taker than the one next to you, you know. And that’s no way to create a world of peace and harmony and wellness. The ancient teachings of the elder society people must be the educators of this world. Because we are the original care-givers of this world and we hold the owner’s manual.

And then we pray. And somehow, in our church-and-state separated religious pluralism and ostensible secularism that barely masks a Christianized nation, prayer is exactly what is needed, feels exactly right—unique to Paul’s tradition and yet with room for the unspecified spiritual diversity present. He thanks the land and the ancestors of this land, inviting each of us to enter the prayer in our own way:

So we should also have a prayer you know…smudge carries up a prayer…prayer goes up to the spirit…my prayer is that we have success, that our prayer is answered. That we have all the things that we need, our birthright to clean water, our languages, the rivers, the elk, the deer the whole circle of life being well…we all have our own prayer for today. Whatever it is, for your family, for a friend, for this earth…we thank the people of this land one more time…honored to be here and do a little bit of work here and prayerfully help [the people of this land] too.

I lift my hands, my eyes closed, the sun angled warmly on the left side of my face. Feeling an overflow of both gratitude and grief, I feel anchored to the smooth ocean stones under my feet and I weep.

I am here today as a part of my own healing. I have wrestled over the several years with the dissonance between my growing awareness of my whiteness and the impact of whiteness on the human and non-human beings of this continent, and the ways I was conditioned into a dominant culture that has dissociated from our nation’s painful history, including “holidays” like this one. Such a disconnect has felt alive and alarmingly painful in my own heart, psyche, and physiology. That’s because I resonate with the understanding that, according to somatic therapist Tada Hozumi, whiteness—rather than being “an essential aspect of having white skin”—is the trauma of painful separation from ancestry. As trauma, it is “embedded so deep in the bones of white bodies and white culture,” and shows up primarily as a “disconnected relationship to the body, particularly to the abdomen, pelvis, and lower limbs.” Loss of sensation in the lower limbs is a hallmark characteristic of trauma, and shows up in the white “cultural body” as a predominance of symptoms such as hyper-rationality, hyper-vigilance, hyper-empathy, and hyper-individualism.

Hozumi makes the link between the embodied states of individuals and their cultural contexts with the term “cultural body” or “cultural somatic context”: that is, “how bodies move, breathe, think, feel, and know themselves within a culture.” This kind of trauma-informed cultural somatic framework is tremendously useful for doing holistic racial justice work. They write: “the simple key to unlocking deep healing of whiteness is cultivating a spiritual practice that can directly address white culture’s impact on white bodies. Once this is in place, the rest, including systemic analysis, comes naturally.”

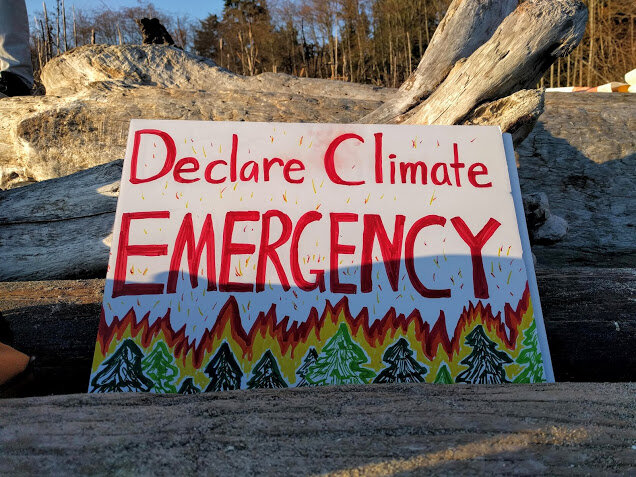

Though without the overt analysis I’m bringing to it, the presence and leadership of Paul and the other elders and non-indigenous organizers present feels aligned with a cultural somatic framework and felt aligned in my body as a rare holistic expression of spiritual activism as an “embodied spiritual practice” that soothed something much deeper in me than just white guilt. After our prayer, we walked the five minutes boardwalk to the house of the governor, where we held signs, drummed and sang chants in peaceful demonstration. Elder Caroline Christmas read a letter to Governor Inslee, stating POSS’ requests regarding the climate crisis, and inviting him to come join our potlatch.

We closed with several elder women laying cedar branches up the path to the Governor’s house, and then holding cedar bundles upon which we could lay hands and speak our prayers. In this way, our very act of protest was also an expression of another, a new, or a very old way of being in relationship to each other and to the world—and even to our “opposition.” The whole day wasn’t just an effort to achieve a specific outcome, but to gently entrain our physical bodies towards a more whole and healthy state through “wisdom gained through being immersed in a culture,” as Hozumi writes, to practice the skills, values and ways of being bodily that whiteness has functioned so well to eradicate: body-awareness, earth-awareness, non-lineality, non-closure, non-perfection, interdependence, to name a few.

At the Sanctuary we aim to uplift and entrain such values and ways of being towards a more harmonious and just world for all of creation. To close with the words of Transqueer Activist, Latinx scholar and public theologian Robyn Henderson-Espinoza: “When we begin to see both the poetry and protest of our current moments as tools for liberation, we learn to embody our reality in a new and meaningful ways. We learn to sing another song, one that is poised for collective liberation.”

“When we begin to see both the poetry and protest of our current moments as tools for liberation, we learn to embody our reality in a new and meaningful ways. We learn to sing another song, one that is poised for collective liberation.”

Sources

Henderson-Espinoza, Robyn. Activist Theology. Fortress Press: Minneapolis, 2019.

Henderson-Espinoza, Robyn. “Gloria Anzaldua’s El Mundo Zurdo: Exploring a Relational Feminist Theology of Interconnectedness.” Journal for the Study of Religion, vol. 26 no. 2 (2013).

Hozumi, Tada. “Whiteness as Cultural Complex Trauma.” https://selfishactivist.com/whiteness-as-cultural-complex-trauma/. Nov. 11, 2017.

Protectors of the Salish Sea. Home. https://protectorsofthesalishsea.org/.

United American Indians of New England. National Day of Mourning. http://www.uaine.org/

Additional thanks to Dr. Jennifer Fernandez for her support in this research and writing effort.